WASHINGTON — A Cambodian monk was interrogated in Vietnam earlier this month and had his passport confiscated for nearly two weeks, for an alleged violation of the country’s controversial cybersecurity law, before authorities returned his travel documents last Friday.

The incident took place in Soc Trang province in southern Vietnam, home to the Khmer Krom community, who are indigenous Khmer, but live mostly in the Southwest of Cambodia’s eastern neighbor.

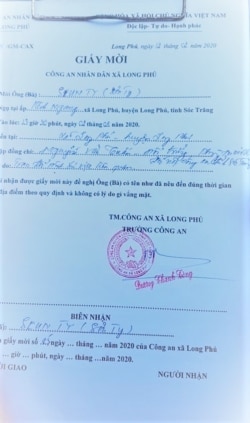

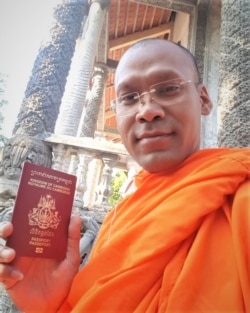

Seun Ty, who is a resident of Phnom Penh in Cambodia, travelled to Soc Trang province’s Long Phu village earlier this month to meet family when was summoned by Vietnamese authorities to discuss an alleged violation of the cybersecurity law.

Seun Ty was born in Vietnam and moved to Cambodia years ago to become a Cambodian citizen, but often visits his family and friends in Vietnam. He is a monk at a Buddhist temple in Phnom Penh and assists Khmer Krom community members.

“On February 2, Vietnamese authorities called me to discuss some issues, but instead they interrogated me and then they charged me of violating a Vietnamese law, the cyber law,” Seun Ty told VOA Khmer last week.

The monk said that the letter the Vietnamese officials used to summon him did not mention any violation of the cybersecurity law, and claimed that he was questioned under false pretenses.

During the interrogation, Seun Ty was asked about news content he had viewed on social media platforms, such as broadcasts and stories from Voice of America’s and Radio Free Asia’s Khmer services, and content highlighting rights violations faced by the community.

The monk added that he was forced to speak Vietnamese during the questioning and was unable to convey to the authorities why he was reading or listening to the allegedly objectionable news.

Seun Ty was asked to admit to his crime and sign a document, admitting to the alleged violation, which he refused to do. Seun Ty said he did not sign the document because he was a Cambodian tourist and that the law should not apply to him.

“They continued to interrogate me and when I did not sign, they seized my passport again,” Seun Ty said, adding that his passport had been confiscated once before in 2009.

Seun Ty said it kept his Cambodian passport for 12 days and returned it only after the Cambodian embassy in Hanoi intervened. However, the verbal intimidation continued even as the Vietnamese authorities decided to return his passport.

“The [police] told me I overreacted by posting the issue on Facebook to get more attention,” he said, adding that they continued to argue in the police station till the officials returned his passport.

Koy Kuong, a spokesperson at the Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said the monk had published information relating to the Vietnamese government, but did not provide additional details of the alleged crime. He did confirm that Cambodian diplomats in Vietnam intervened to resolve the issue.

Huynh Thị Diem Ngoc, spokeswoman of Soc Trang Province People’s Committee, and Ms Kieu, of the People’s Committee of Long Phu Commune, were contacted by VOA and said they were unaware of the case. VOA Khmer attempted to reach provincial police official multiple times for comment.

“The information so far is that the venerable [monk] was charged with violating Vietnamese law by publishing information against the Vietnam government,” Koy Kuong said, declining to provide additional details.

While the Khmer Krom community faces rights violations in Vietnam, they do have a complicated relationship with the Cambodian government. Phnom Penh has been tolerant of allowing members of the community to freely cross the border, but have also not clearly outlined their position on citizenship for the Khmer Krom nor have been tolerant of any critique of their eastern neighbor from the community.

Politically, the Khmer Krom community generally are viewed as aligned with the now-dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party, which had taken up their issues at the national level.

Prak Sereyvuth, chairman of the U.S.-based Khmer Krom Federation, said Seun Ty’s case was another incident that underlined the rights violations faced by the community in Vietnam.

He added that the behavior of the Vietnamese authorities illustrated how they turned the mundane act of viewing or listening to the news into a potential national security issues, in order to enforce the controversial law.

“These are not the acts of terrorism but Vietnam uses these methods to [crackdown],” said Prak Sereyvuth.

The controversial law went into effect in early 2019 and required internet companies to open offices in Vietnam, store local user data and to hand over any information requested by the government that had been deemed objectionable to offensive.

“Cybersecurity means the assurance that activities in cyberspace will not cause harm to national security, social order and safety, or the lawful rights and interests of agencies, organizations and individuals,” a copy of the law reads.

Opponents of the law said it was another instance of the one-party communist state’s attempts to stifle free speech and to crack down on dissent. The law also allows authorities to censor these views on social media.

Human Rights Watch’s Phil Robertson said the worrying aspect of this incident was that Seun Ty was seemingly under surveillance, which resulted in finding the allegedly objectionable social media news content he was viewing.

“This is a matter of freedom of expression and for him to face any sort of charges for simply conveying information about the rights abuses and the problems face by the Khmer Kampuchea Krom in Vietnam, you know, it’s a clear violation of freedom of expression,” he said.