WASHINGTON — The United States and European Union may have waning leverage over Cambodia as it slides further into China’s orbit, however Cambodian-Americans fear that upcoming elections could prompt further erosion of Phnom Penh’s relations with the West.

And the fallout is likely to hurt ordinary Cambodians rather than the ruling party elites who Western officials blame for backsliding on democracy and human rights in recent years, a number of political engaged U.S. Cambodians told VOA Khmer.

The most controversial aspect of July’s national election is the decision last month to bar the main opposition Candlelight Party from participating. Cambodia’s most prominent opposition leaders also remain under house arrest and in exile, while dissidents of all stripes have been jailed or intimidated into silence.

"I can clearly see that the outcome of that election is invalid,” said Larry Seng, who lives near Seattle, Wash. and supports the opposition, noting that while other parties are registered for the election, none represent serious competition to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

He worried that the main tools available to the U.S. and E.U. — withholding or restricting trade benefits — risk compounding the economic struggles of working-class Cambodians, while inflicting minimal pain on Cambodia’s leaders.

"The international pressure is nothing more than economic pressure, and that economic pressure is affecting Cambodians, the poor, the less resourceful, making life even more miserable," said Seng.

He said the CPP “do not care about the suffering of the people, as long as the members of that party live comfortably,” thanks to the continued support of communist countries such as Vietnam and China.

Since 2017, when the CPP began its crackdown on the opposition and passed a series of election reforms, the U.S. and E.U. have urged the government to reopen democratic space and respect basic political rights.

The main stick has been the threat to withdraw their respective Everything But Arms (EBA) and Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) trade preferences for lower-income countries, which account for hundreds of millions of dollars every year to Cambodia’s export sector.

And to some extent, they have already made good on those threats, after the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party was dissolved and the CPP effectively returned to one-party rule following the 2018 national election.

The E.U. officially suspended trade privileges for 20 percent of Cambodian exports, affecting the garment, footwear, travel goods, and sugar sectors — which together employ some 1 million workers.

The U.S. preferences, meanwhile, expired in December 2020 and have not been renewed, meaning Cambodia is losing out on billions in duty-free or low-duty exports (though America remains its largest export market).

The E.U. Parliament in March passed a new resolution threatening to further restrict EBA privileges for Cambodia “if the 2023 elections deviate from international standards or violations of human rights continue.”

However, Prime Minister Hun Sen thumbed his nose at the threat in a speech to factory workers in June, noting that the entire trade scheme is expected to wind down in the coming years.

“And the EBA is going to end in 2027 anyways. So, if Cambodia loses it, it’s not a problem. We do our best, don’t use someone’s oxygen too much so when they pull out the oxygen, we can no longer breath,” he said.

Un Sokhom, a Lowell, Mass. resident and a former opposition party official, said the CPP’s reliance on China was the reason Hun Sen could brush off the loss of trade benefits.

"It does not affect the government, but more importantly, it affects the people,” he said.

Many opposition supporters are calling on Western democracies to refuse to recognize the Cambodian government unless it agrees to concessions including allowing Candlelight party to participate in the election.

“I firmly believe that it is not just me, that many of us Cambodians have the same beliefs as me, and that the international community is well aware of the current situation,” said Larry Seng. “I do not think they will legitimize the election.”

However, ruling party spokesman Sok Eysan shrugged off that possibility in an interview with VOA Khmer.

“There is nothing to worry about because this is the internal issue of Cambodia,” he said, noting that despite international outrage following the 2018 election, no countries withheld recognition of the new government.

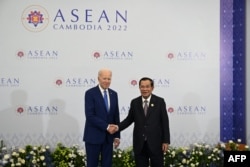

And he noted both the U.S. and E.U. have since welcomed Hun Sen for summits along with other Asian leaders, while Cambodia has been involved in efforts to strengthen economic ties between the regions as well.

In Suon, a social worker from Stockton, Calif. and a former CNRP supporter, said he didn’t believe the CPP’s bluster — arguing that damaged relations with Western powers posed deep risks for the ruling party.

"The people at the grass root are miserable. Not only the people, but also businessmen, the ordinary traders, because they have lost the rights to protest, to seek the law, to seek justice in the conduct of economic business," In Suon said.

"Even though Cambodia says, 'Oh, you do not have to depend on the free world countries to survive.’ It is true on the surface, but in reality, it is not so.”

In Suon said the U.S. and E.U. continue to be the biggest markets for billions of dollars worth of Cambodian products — from agriculture, sport, and garments — and could not be easily replaced by other countries or regions.

Sek Kosol, chairman of IKARE in St Paul, Minn., said Cambodia’s government had a tremendous opportunity to generate goodwill among Cambodians worldwide if it opened political space for all parties, including those opposed to the government, to participate in the July 23 election.

He compared the situation to U.S. politics, in which the main parties disagree about most things, but occasionally find some common ground.

“So, in Cambodia, if we do not like the opposition party 80 to 90 percent or if the opposition does not like the ruling party 90 percent, we can find 10 percent that we can work together and we focus our time to do that 10 percent,” he said.

Sek Kosol said the CPP should stop framing the political “opposition” as a threat to the country.

“So, the word 'opposition' does not mean that they are against our nation…[rather] they are against the absence of democracy, human rights, humanity in our country, and if we have all important points, it will make other people in other countries value us accordingly."

However, Vibol Touch from High Point, N.C., — a longtime opposition supporter turned critic — said the question of international legitimacy would have little bearing on the CPP’s actions around the election, or ultimately the global response.

"I do not believe that the United States will withdraw its embassy from Cambodia or any other country in Europe will withdraw its embassy from Cambodia. I do not believe that,” he said.

Additional report by Han Noy in Cambodia