PHNOM PENH — The Phnom Penh airport shuttle has had a slow start over the last 18 months. And that has nothing to do with its top speed of 25 kilometers per hour.

One morning in July, the train’s engines were rumbling, ready for the early morning ride. The blowing of the horn signaled it would shortly begin the 10-kilometer journey from the Royal Railway Station in the center of the city to the Phnom Penh International Airport.

But, there were no passengers occupying the blue, white and yellow striped carriages for the 7 a.m. ride.

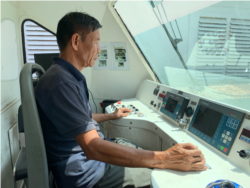

“The train still takes off even without any passengers,” said 60-year-old train driver Choeng Chanthy.

The airport shuttle is part of a project to revive Cambodia’s degraded network of railway tracks. Apart from the airport service, there are weekend passenger services that run from Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville, and more recently, the tracks have been upgraded to allow for services to Banteay Meanchey province, extending all the way to Bangkok, Thailand.

The railway concession is run by Royal Railways, which is owned by prominent business tycoon Kith Meng. However, the airport shuttle has struggled to attract passengers or residents looking to beat the traffic on streets leading towards the airport.

John Guiry, CEO of Royal Railways, said the airport service needed to be advertised better and to a wider customer base, because it was a convenient option for travelers looking to beat the traffic.

He said the company should also target Phnom Penh residents, rather than only air passengers, to use the service for their daily commutes.

“The traffic, especially along Russian Boulevard is so terrible. People need one to two hours to arrive at the airport,” Guiry said. “However, now we need only 30 minutes to get there [on the train].”

Guiry’s pitch for using the train service is finding some resonance with travelers.

Raksmey Chea Chandara, one of only two passengers traveling on an airport shuttle in July, stepped off the train with his suitcase and a cold drink in hand, ready to board a flight to Laos.

“There wasn't any traffic jam when using the train,” Chea Chandara said. “The traffic jams are now really bad. That's why I wanted to try riding the train and it was nice.”

However, with a single line operating in the city, it could be hard to convince daily commuters to use the service. A more connected public transport infrastructure would help drive more residents to use the airport service.

Ly Sreysros, a Phnom Penh-based sociopolitical analyst, said the route was short and had no stops between the airport and railway station, reducing the appeal for local commuters. Whereas, social analyst Meas Nee said the city needed to centralize or ensure easy connectivity within the transportation infrastructure to ensure ease-of-use for Phnom Penh residents.

“The train station should be around the areas where there are city bus stops,” Meas Nee said. “It is more convenient for people who come from different areas in the city to meet at one central place for the ride to the airport.”

Another recent addition to the public transport system are buses. However, similar to the train service, the public bus system was not very popular with residents and running a loss in 2018, according to Phnom Penh Governor Khoung Sreng.

Despite these challenges, there may be a glimmer of hope the train service could convince more Phnom Penh residents to adopt the use of trains.

Guiry said Royal Railways was partnering with China Southern Rail to build a monorail system that would again connect the airport and the railway station, but a second line that would end at NagaWorld casino.

Sambo Rith Onyka, who lives near the airport, was taking the train from Phnom Penh railway station in late July. Rith Onyka works at a company close to the railway station and said the airport route suits her travel needs.

Getting off at the airport, she was pleased with the one-hour ride, but wasn’t impressed with the 30-minute wait for the train. Rith Onyka felt that while the ride times by road and train were the same, the latter provided a more comfortable option.

The new carriages are equipped with air-conditioning and WIFI, comforts not available if Rith Onyka were to use a tuk tuk or motorcycle.

“It's still one hour [travel time] since I had to wait half an hour before departing, but for the other half hour, I sat and enjoyed the view from the train,” she said.

Choeung Chanthy: Rready to call it a day

From being a locomotive workshop technician to eventually running the maintenance services at Royal Railways, Choueng Chanthy’s life is emblematic of the aspirations of post war Cambodians.

It took Cambodia years to begin restoration of its railway network, after it had been destroyed during the civil war, leaving most of the infrastructure unusable. Choeung Chanthy’s career followed a similarly halting trajectory.

After joining the Ministry of Public Works and Transport railway workshop in the early 1980s, it took him four years and multiple attempts to get the job he would eventually be most passionate about - being a train driver.

“After working in this field for some years, I started to naturally love this job and I feel lucky about that,” Chanty said.

But, the seemingly glamourous job did not pay well. Choeung Chanthy admits that in order for him to do the work he loved, his first wife had to continue working at her seafood business, despite her failing health. Choeung Chanthy also chipped in, delivering fish at dawn before heading to work at the railway station.

When his wife could not work, the job he loved took on a higher purpose - as the sole income for his family. When times were tough, Choeung Chanthy admits to taking out loans to buy houses for his children.

Sitting next to a train in July, the smell of petroleum thick in the air, Choeung Chanthy said his children have pretty much settled down.

The train driver, along with his wife, ensured their children were married, educated and have jobs, giving them the opportunity to prosper, much like with his first job at the workshop.

And as his responsibilities towards his family wane, Choeung Chanthy is considering making the hard decision of giving up his passion – being around trains.

“There is nothing to do anymore, just look after grandchildren, drive them to school, and go to the pagoda,” he said, with an air of contentment.