With the risk of arrest or injury high for those reporting on the Myanmar junta, many journalists have fled to borderlands or neighboring countries.

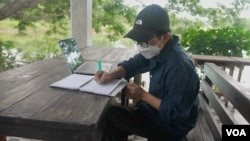

From there, journalists like Hsa Moo try to keep news flowing to their audiences.

Working from the Thai border, Hsa Moo documents evidence collected directly from her sources in Myanmar’s Kayin State. Her coverage includes military clashes and how the military coup is impacting communities and internally displaced people or IDPs.

It’s a tough beat. Airstrikes from Myanmar military warplanes and helicopters make travel risky in what is one of the hardest hit regions.

Under attack

Normally controlled by the Karen National Union army’s 5th Brigade, the region has come under attack from junta forces.

“When you go, you face the Burmese army shelling and everything,” said Hsa Moo, as she edited photographs of a bombed village.

But she added, “When you see the [displaced people] and when they see you, they also feel very happy because they know that somebody, some people, still care for them,”

Hsa Moo contributes to the Karen Peace Support Network, a civil society network for one of Myanmar’s ethnic groups. Made up of 30 organizations in Myanmar and Thailand, the network provides support and information to communities in the region.

Like Hsa Moo, many Myanmar journalists have chosen to work in neighboring countries. Some are trying to avoid arrest. Rights groups say the junta is using laws to target critics.

“If you are inside Burma [Myanmar] they will just block or censor everything. The government has a propaganda newspaper and the TV shows, but that is all the lies,” Hsa Moo said.

The junta is also proposing cybersecurity legislation that could block the use of Virtual Private Network or VPNs.

With access blocked in Myanmar to social media and other websites, VPNs have offered a workaround for those wanting access to information.

Many had come to rely on social media as a source of news. When Myanmar opened up in the early 2000s, a number of independent media turned to Facebook as a platform to post news from their regions.

“Myanmar is not like other countries. Before, it was called the Facebook nation because 99% of the public use Facebook so that is why [military] also tried to ban Facebook,” said a Kachin news editor, who goes by the pseudonym Seng Li.

Seng Li oversees a network of journalists, mainly in an area under the control of the Kachin Independence Organization.

Both Kachin and Kayin states have territory controlled by ethnic armed groups who want autonomy.

Apart from a 17-year cease-fire, the Kachin Independence Organization and its military arm, the Kachin Independence Army, have been at war with the Burmese army since 1961.

Rights groups believe the junta targets media to try to silence criticism.

“For the junta, the enemy is now anyone reporting a narrative that differs from the propaganda pushed out by the ludicrously named Tatmadaw ‘True News’ team,” said Phil Robertson, Asia deputy director for Human Rights Watch (HRW). Tatmadaw is the official name of Myanmar’s armed forces.

“Journalists still operating inside Myanmar are now almost all reporting from hiding, where they courageously continue to try to do their work despite huge obstacles and the risk of arrest at any time,” Robertson told VOA.

Arrest risks

Military spokesperson Gen. Zaw Min Tun has denied that the junta arrests journalists for their work.

Media workers are arrested only “if they are involved in violence or anti-military activities or treason,” he told VOA.

The regional group Reporting ASEAN however has documented over 120 arrests of journalists since the military seized power in February 2021. Of those, at least 48 are still in custody, data show.

Authorities sometimes add additional charges to those already detained, potentially adding years to their prison term.

Han Thar Neing, co-founder of news website Kamayut Media, received a two-year sentence on March 21, on charges of spreading false news.

Now, the 40-year-old faces an additional charge under an Electronic Transactions Law that could add seven years to his sentence.

It’s an unexpected turn of events for his family, who already suffer from chronic stress, unable to see him in person at Yangon’s Insein Prison.

Han Thar’s family can deliver limited food supplies to him twice a month, through the prison officials, but cannot see him.

His sister Kyi Thar says her heart sinks every time she sees footage of her brother on the news, sometimes in a blue prison uniform, his hands and ankles shackled.

“I hope for the future, journalists like my brother — including other Myanmar journalists — will be treated like the other country’s journalists,” she said. “They are journalists doing their job of covering the news and they don’t commit any crimes.”

International bodies have criticized Yangon’s treatment of prisoners held in Insein prison, including detained activists and reporters.

“Myanmar's prisons are among the poorest and most brutal in the Southeast Asia region, so the imprisoned journalists must be facing the equivalent of hell on earth,” HRW’s Robertson told VOA.

“Incarcerated journalists should be allowed regular, unhindered access to relatives, and to legal counsel, and be made immediately eligible for release on bail,” Robertson added.

Despite the risks that reporting on life in Myanmar brings, reporters continue to cover the conflict, both from within and outside the country.