Sum Rithy, one of a few survivors of a Khmer Rouge detention center in the northern party of the country, says he remains disappointed in the UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal.

The court is not investigating crimes at that center, which was in Siem Reap province, as it prepares to try former leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.

“My regret is that if the northern prison is not be brought to trial, I will never close my eyes,” Sum Rithy said in an interview. “In fact, there should be digging up of that place and more charges put on the two defendants.”

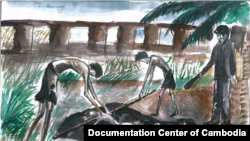

Sum Rithy was accused of spying for the Central Intelligence Agency—a common charge among Khmer Rouge—in the 1970s and imprisoned in Siem Reap. He was forced to bury bodies he says are still in mass graves in the province. The court should examine these sites, he said.

“All are there and have not been dug up, so does it mean justice for me if the court leaves out the site?” he said.

Latt Ky, a tribunal monitor for the rights group Adhoc, said there was once some discussion of the incorporation of such crime sites, filed by civil parties, but the court excluded some without sufficient explanation to victims. That has caused “serious resentment” from some victims, especially those dealing with mental health issues and trauma, he said. Victims like Sum Rithy have made a lot of efforts, including psychologically, to come forward and tell their stories, Latt Ky said.

Pich Ang, the leading civil party lawyer for the tribunal, said he met with Sum Rithy two times to discuss with him the court’s decision in not selecting his crime sites. The court had to make some choices for the sake of expediency, especially in Case 002, which charges aging leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan of atrocity crimes. Other crime sites took priority, Pich Ang said.

“The big difference in crimes means that there are crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocidal crimes,” he said. “This is the judges’ selections, to have representations of the serious crimes, and in site, the judges scrutinized whether they had different crimes or not.”

The tribunal defined the scope of the current phase of the trial in April, choosing sites that were “reasonably representative” of crimes in the indictments of the two leaders, including forced marriage, rape, genocide against Cham Muslims and Vietnamese minorities. Those include the security centers of S-21; Kraing Ta Chan; Au Kanseng and Phnom Kraol. They also include the January 1 Dam work site, the Tram Kok cooperative, and others.

Sum Rithy’s site was not among those listed, which has been a disappointment, especially because he won’t be able to testify against the accused, he said. “I wish to send the message to notify the UN to bring the northern site to trial,” he said in an interview. “I wish to inform Mr. Ban Ki-moon and want my words to be heard by him as the UN chief.”

Peter Maguire, an America law professor and an author of a book about the Khmer Rouge, said the tribunal process made promises that were not fulfilled—which is not uncommon.

“It’s a great disappointment in many of these cases,” he said. “For example, in (Slobodan) Milosevic’s case, they spent hundreds of millions of dollars and they didn’t even finish the trial within the lifetime of the defendant. So the Khmer Rouge tribunal is very similar to many of these other courts. They came in the wake of the Cold War, and they’ve all been very, very imperfect.”