PHNOM PENH - A French Catholic priest testified before the UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal, which has resumed hearings following the death of defendant Ieng Sary.

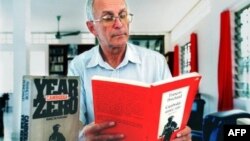

Francois Ponchaud, 74, who arrived in Cambodia in 1965, told the court the Khmer Rouge were known for atrocities in the villages before taking over Phnom Penh in April 1975.

“The Khmer Rouge terrified us,” he said. “Even as they watched us, it seemed they fired at us with their eyes.”

But he also said the US and UN had been “indifferent” to the suffering of the Cambodians.

Ponchaud’s testimony marked a resumption of hearings for the tribunal, which has struggled over the last few months with funding problems and the death of Ieng Sary, who had been on trial in this case alongside Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan for atrocity crimes, including genocide.

Ponchaud, a Khmer Rouge historian who wrote “Cambodia: Year Zero,” described the emptiness of Phnom Penh following the Khmer Rouge takeover. He had not seen anyone killed when the Khmer Rouge came into the capital, but the disposition of the insurgents was well known, he said.

“Since the year 1973, we knew clearly what the Khmer Rouge did in the rice fields,” he said. “We knew when they seized a village, they burned the houses, they killed the chief of the village and people in power, and they expelled the people to the forest.”

But Ponchaud gave some of his harshest criticism to Western powers for ignoring the plight of the Cambodian people.

“I feel ashamed of the United Nations,” he said. “I’m actually ashamed that the United Nations is coming in and taking part in the prosecution of Khmer Rouge leaders.”

Francois Ponchaud, 74, who arrived in Cambodia in 1965, told the court the Khmer Rouge were known for atrocities in the villages before taking over Phnom Penh in April 1975.

“The Khmer Rouge terrified us,” he said. “Even as they watched us, it seemed they fired at us with their eyes.”

But he also said the US and UN had been “indifferent” to the suffering of the Cambodians.

Ponchaud’s testimony marked a resumption of hearings for the tribunal, which has struggled over the last few months with funding problems and the death of Ieng Sary, who had been on trial in this case alongside Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan for atrocity crimes, including genocide.

Ponchaud, a Khmer Rouge historian who wrote “Cambodia: Year Zero,” described the emptiness of Phnom Penh following the Khmer Rouge takeover. He had not seen anyone killed when the Khmer Rouge came into the capital, but the disposition of the insurgents was well known, he said.

“Since the year 1973, we knew clearly what the Khmer Rouge did in the rice fields,” he said. “We knew when they seized a village, they burned the houses, they killed the chief of the village and people in power, and they expelled the people to the forest.”

But Ponchaud gave some of his harshest criticism to Western powers for ignoring the plight of the Cambodian people.

“I feel ashamed of the United Nations,” he said. “I’m actually ashamed that the United Nations is coming in and taking part in the prosecution of Khmer Rouge leaders.”