Editor’s note: This is one in a series of articles looking at Chinese involvement in Africa. Also read about infrastructure deals and business opportunities.

In late June, top military officials from Mali, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and dozens of other African countries gathered to discuss defense strategies and security threats.

The meeting didn’t take place in a major African city, but thousands of kilometers away, in Beijing, China.

The occasion was the inaugural China-Africa Defense and Security Forum, a high-profile showcase of expanding military partnerships hosted by China’s Ministry of National Defense.

The forum, which concluded July 11, solidifies China’s standing as a key security partner for Africa and coincides with a raft of economic and political moves that have deepened its involvement across the continent.

Ideology, economics, politics

Paul Nantulya, a research associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies who focuses on China-Africa relations and security, told VOA that China’s military involvement in Africa blends ideology, economics and politics.

China’s presence on the continent dates back to the liberation struggles of the 1960s, when it supported anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements in South Africa, Algeria, Sudan and other countries based on what Nantulya called “ideological concerns.”

When former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping came to power in the late 1970s, unprecedented reforms set the stage for China’s ascent as an economic powerhouse.

China’s new global posture influenced its engagement in Africa, Nantulya said, bringing economic and political layers to relationships that had previously been one-dimensional.

“The military engagement that China has on the continent has become much more complex than merely just an extension of its ideological concerns,” Nantulya said.

“Increasingly, we’re also beginning to see military-to-military exchanges between African countries and China, and these exchanges cover a whole range of issues, from peacekeeping to disaster response, to military building, army building, professional military education,” he added. “So, it’s a much bigger portfolio.”

Clear goals

African military officials at the defense forum told CGTV, a Chinese state-run broadcaster, that they have well-defined expectations of their partnerships with China.

“What we require from China, which is made very clear, is for them to provide us with the partnership, with the support, with the expertise, with the technical capability, with the capacity-building, with infrastructure, for us to be able to do the job ourselves,” said Lt. Gen. Masanneh Nyuku Kinteh of the Gambia Armed Forces.

But if African nations see in China a strategic partner, China sees, at least in part, potential customers. That’s because China is a major player in the global weapons supply chain, Nantulya said, and it’s looking for markets.

Chinese manufacturers have used their growing presence in Africa, along with generous government subsidies, to produce military hardware that’s both cheaper and easier to maintain than their competitors.

Whereas Western countries focus on heavy hardware — jets, tanks, rockets — China’s niche has long been small arms, including pistols and AK-47 assault rifles, Nantulya said.

They sell these, along with ammunition, bullet-proof armor and unmanned aerial vehicles, not just to African militaries but also to police and intelligence forces.

One example of a close arms relationship is with Sudan, a country whose military industry China helped develop. Algeria, Mozambique and Zimbabwe also import many Chinese arms. And that portfolio is becoming more diverse, including tank deals and accompanying technical training with South Sudan and Uganda, Nantulya said.

Party-to-party

China’s military engagements span the continent, from traditional partners such as Angola, Libya and Tanzania, to more recent relationships with Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti.

In each case, China seeks to strengthen its military-to-military connections with party-to-party ties, Nantulya said. “China invites officials of these ruling parties in these different countries to Beijing. This is a program that is run by the [Central] Party School,” he added, referring to the institution that trains officials for the country’s Communist Party.

Through this year-round program, China promotes its ideologies and large-scale initiatives, combining political propaganda with defense strategy and tactics.

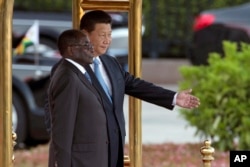

One example in which many saw Chinese political and security interests mesh was the abrupt fall from power last November of Robert Mugabe, who had led Zimbabwe for 37 years. Many analysts suspected that China played a role in what some considered a military coup.

A visit by Constantino Chiwenga, then the chief of the military, to Beijing days before Mugabe was put under house arrest stoked those rumors. But shortly after Zimbabwe’s military seized control, Geng Shuang, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson, told Reuters that the visit “was a normal military exchange.”

Chiwenga now serves as Zimbabwe’s vice president.

‘Cult of defense’

China casts itself as a different kind of partner for African countries eager to see their sovereignty respected. Rather than make development aid contingent on political reforms or project overt military power, China pursues its security goals indirectly.

One venue that’s served as a springboard to a deepening military presence is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s trillion-dollar global development program, which has been the backdrop for many of China’s emerging relationships in Africa.

The BRI projects, including railways, dams, ports and a sprawling new free-trade zone in Djibouti, have the potential to accelerate Africa’s industrialization. In many cases, they also entail an ongoing Chinese presence and an investment that needs protecting.

“This is a huge — a massive — footprint,” Nantulya said. “And so China is coordinating its military approach to be able to secure some of those interests.”

China has also become more involved in peacekeeping missions to expand its military footprint.

“They’ve been much more willing to deploy peacekeepers in places like Sudan, in Darfur, [and in] South Sudan. They’ve been much more willing to take those kinds of risks. But those kinds of risks also come with demands,” Nantulya said.

No-strings-attached engagement without political preconditions has, so far, been an effective strategy for China. But it has also restricted the moves China can make and how it presents itself to prospective partners.

“China has been captive to what one would call a ‘cult of defense,’” Nantulya said.

That would preclude making pre-emptive strikes or other overt shows of power. China considers its base in Djibouti, for example, a “logistics facility.”

But China is part of an elite group of countries that has such overseas bases. And at least one stipulation accompanies all its deals: Countries must sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan, a country that China considers its own territory.

Equal partner?

To build solidarity, China presents itself as a developing country on par with partners in South Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Maj. Gen. Ibrahima Dahirou Dembele from Mali highlighted shared interests at the Defense Forum, saying, “We are close to China both culturally and historically, and in facing challenges.”

But the size of China’s economy surpasses all of Africa combined, and a recent report by The New York Times on a port transfer in Sri Lanka shows that China can be an aggressive strategic partner.

In the past decade, China has embraced a more assertive stance around the world, Nantulya said. That’s evident in its intelligence, defense and security strategies, and embedded in its foreign policy.

But China’s “equal partner” narrative has endured.

During a Defense and Security Forum speech that aired on CGTV, Wei Fenghe, China’s national defense minister, said, “China and Africa’s countries are developing nations. It’s truly fair to say that we are for a community of shared future.”

It’s a sentiment that recalls China’s ideologically driven involvement on the continent in the 1960s and continues to resonate, despite ambitions that have become far bigger and more complex.