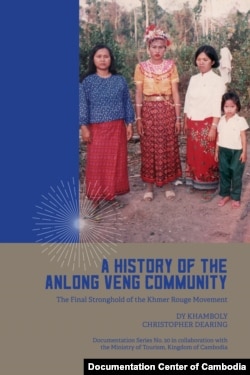

The Documentation Center of Cambodia is publishing a new book this month on the former Khmer Rouge stronghold of Anlong Veng.

The authors say “A History of the Anlong Veng Community: The Final Stronghold of the Khmer Rouge Movement,” will contribute to national reconciliation in Cambodia, as well as in other countries that have similar experiences.

Situated about 125 kilometers from the city of Siem Reap, Anlong Veng was home to the top Khmer Rouge leaders including, Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and Ta Mok. Today it’s home to 9,000 families, or about 42,000 people.

Although the Khmer Rouge regime was ousted in 1979, Anlong Veng continued to be under Khmer Rouge control on and off for almost 20 years, until reunification with the government in 1998.

Yim Phanna, the governor of Anlong Veng, told VOA by phone that he joined the Khmer Rouge in 1971 at age 17, in response to the call from the late King Norodom Sihanouk to help topple the Lon Nol government and push the Americans from Cambodia.

“I heard the former king, so I left school to join the Khmer Rouge army with the others,” he said.

Under the Khmer Rouge, from 1975 to early 1979, an estimated 1.7 million people died of disease, starvation, hunger and extrajudicial killings.

The former Khmer Rouge commander said he regrets his decision to join the Maoist movement.

“I’m very regretful, because what we’ve done was a waste,” he said. “There were so many killings of our own people.”

Such regret might surprise some people, who think all Khmer Rouge were evil.

In order to have a better understanding about Anlong Veng and to help develop this area into a tourist attraction, the Documentation Center is publishing the book in cooperation with the Ministry of Tourism.

Dy Khamboly is the senior researcher at the center and the co-author of the book. He said the book aims to be the starting point for former Khmer Rouge cadres and their victims to better understand one another.

“It starts with learning about each community, and each person clearly in order to understand and to forgive so that we can prevent future genocide through learning,” he said.

Another goal of the book is to document the Khmer Rouge regime from the beginning to the end, he said.

Chris Dearing is the other co-author of the new history book. In an interview at the VOA offices in Washington, Dearing said one of the key findings in the book is that one cannot conclude that all former Khmer Rouge cadres were evil, because some of them are victims of the regime as well.

“I think one of the important part of this book was to bring out the human aspect, the human faces behind the movement,” he said. “There certainly was evil. There were certainly criminals and true perpetrators, but there were also victims. History is not as simple as victims and perpetrators.”

Dy Khamboly agrees. He said some former Khmer Rouge cadres also suffered under the regime they had fought for.

“Some said they joined the movement not because they liked the movement but because they were coerced or forced to join and did not have a chance to get out,” he said. “Therefore they had to live with the Khmer Rouge regime on Dangrek Mountain and then went to Anlong Veng, until 1998.”

The Khmer Rouge regime was known for its secrecy. However, in the book, a number of the former Khmer Rouge cadres describe in detail events, including the struggle between the Khmer Rouge top leaders, especially toward the end of it.

The Documentation Center spent over 10 years researching and mapping out the Anlong Veng area and over two years interviewing and writing the book, Dearing said.

Dy Khamboly said his research team had to spend a lot of time in Anlong Veng before they earned the trust of the former Khmer Rouge cadres. “I interviewed some people for five hours. For one man, it was seven to eight hours. Once he fully trusted me, he spent three days speaking to me. My team and I went to Anlong Veng, if I remember it correctly, four times, and each time we spent as long as two weeks there to interview people.”

Dearing said it took some convincing to get people to talk.

“We said that this is the history of the community, and it’s important to get the history on record, because the future generation doesn’t really understand the history,” he said. “This is an important piece of Cambodia’s history, and we don’t want it to simply pass into the sands of time. We want to capture it.”

Dy Khambody said that besides being a community history book that reflects the lives of the people there, the book is important in another aspect. “This book is also a model for the other communities to look at and to use as a lesson, so that they can write a history book about their own community to learn about what had happened.”

Dearing said he hopes the book will serve as a model for other countries as well. “One of our goals in this project was to use it as a template for other communities, not just in Cambodia but even for overseas, in other countries that are suffering from the same problems,” he said.

The book, which will be printed in English and Khmer, comes out at the end of January.