Editor’s note: David P. Chandler has written six books on the history of Cambodia, along with numerous academic articles. His first book, “A History of Cambodia,” has been translated into multiple languages, including French, Khmer and Thai. At the Association of Asian Studies 2018 annual conference two months ago in Washington DC, Chandler’s scholarly work on Cambodia’s history was recognized with the Award for Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies. It is the U.S.-based association’s highest honor. Chandler is an emeritus professor at Monash University. He served as a U.S. Foreign Service officer in Cambodia from 1960-62. The 85-year-old scholar sat down with VOA Khmer’s Chetra Chap on the sidelines of the conference to discuss Cambodia’s relationship with China, authoritarianism in Southeast Asia, and his career as a historian. This is the first of two interviews VOA Khmer conducted with Chandler on March 24. It has been edited for length and clarity. The second interview will be posted later this month.

What do you think about China’s rising influence in Cambodia today and in the near future?

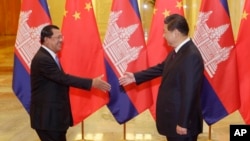

I think China’s influence in Cambodia today is very strong, and the Cambodian government is perfectly happy with it. Cambodia is not a puppet of China. It’s not serving China’s interests, necessarily. But when an issue comes up that is in China’s interest, Cambodia is going to—as they did with the South China Sea a few years ago—they are going to be a friend of China. It’s their most friendly donor. It’s part of a campaign that China’s had for years of pushing into the countries of Southeast Asia and Africa and Latin America with aid programs that will gain friendship from these governments. They’ve been very successful. Whether it’s a positive development or not, I can’t say, but I don’t think it is going to stop for the foreseeable future. They are not going to withdraw their friendly aid to Cambodia in the future.

Looking at history, does the Khmer Rouge teach us anything about relying too much on China?

Well, people would say it’s a different China now and Hun Sen’s government is not a Khmer Rouge government. And I don’t think it’s a matter of relying or copying. The Khmer Rouge copied China, and China was an ideological model. That is not happening [now]. Cambodia is not a communist country. China is still a communist country. But the friendship [between] the two states, I think it’s okay for both of them as far as I can see.

In terms of economic investment, there are currently a lot of Chinese businesses coming into Cambodia, buying land, doing all kinds of economic activities. Does this pose a concern for the Cambodian people?

Oh, I think it should be, but I don’t think there’s much that can be done about it. I don’t see who is going to come to the defense of the Cambodian people against business interests, capitalism if you like, Chinese interests. I don’t think it is a very healthy development to have that much land transferred, but I don’t see who is going to come to their help. And maybe in the long term, it will be positive like the Western European industrialization: There were a lot of casualties, but then you ended up with a very booming economy in the late 19th century. And maybe that’s where we’re driving at.

I don’t think it is a very healthy development to have that much land transferred, but I don’t see who is going to come to their help. And maybe in the long term, it will be positive like the Western European industrialization: There were a lot of casualties, but then you ended up with a very booming economy in the late 19th century. And maybe that’s where we’re driving at.

If you were to give some suggestions to the Cambodian government in dealing with China, what would you say?

How can I give suggestions to the Cambodian government? I think the current regime is very happy with the arrangement, so there’s no advice. My advice maybe, to another government, which is not going to happen, is that maybe you should be more cautious. But I have no right to advise the current government and I don’t think they are paying any attention to anyone who says you should pull back from this very profitable arrangement that they’ve entered into.

So, in the regional and international context, what does Cambodia moving toward China and moving away from the Western community mean for Cambodia?

Well, they never were that close to the Western community. They always would prefer Asian alliances. They’re an Asian country, and Asia countries prefer friends in Asia. What it means in ASEAN, I am not sure. It might have some effect on Cambodia’s membership in ASEAN. Some of the other members, Indonesia for example, might be just a little nervous about the size of Chinese investment and influence in Cambodia. That may have ramifications, I don’t know. I don’t think it’s got anything special for Cambodia’s future that I can see at the moment.

Now, let’s look at the overall future of Cambodia in the long term. Given its history with powerful kings, communist regimes and recent close ties to communist superpowers, will Cambodia be able to function as a democracy?

I don’t see that in the immediate future. Every country in Southeast Asia has always been or has become authoritarian in the last few years. It’s a worldwide trend. How long is this going to happen or continue? I don’t know. There are some good signs in Europe that, maybe, it’s not going to be that bad. But there’s a trend toward authoritarianism in the world today. The Philippines and various other countries have become authoritarian. The Cambodian government—except, of course, under colonial rule—has always been authoritarian. It’s never been democratic. It’s never been an open, competitive political society. I don’t see that as happening in the future, which is too bad, from my point of view, but I am not Cambodian.

Is there a way that we can actually make it happen?

No. Well, I mean, who is going to take up arms? It would have to be something like that. I certainly don’t expect anybody to want to do that because they will be crushed. Anybody who took up arms against the Cambodian [regime] would quickly be put out of business, so it’s not going to happen violently. I don’t see it happening peacefully in the foreseeable future because the electoral process has been taken over, pretty much, by the government. It’s not an election where someone else is just going to have a chance to—where there will be a regime change. That is exactly what Hun Sen is absolutely opposed to: regime change. There’s not going to be any.

So, looking at that goal of trying to change, Cambodian youth and people are very active in civic issues. What kind of role do you see them playing?

They are going to continue to be active and I am certainly not in a position to give advice, but I am moved by their activity and by their interest, but I can’t see how that activity and interest can have any positive regime alteration effects, the way the regime is behaving at the moment. This is not a good time for that type of activity.

Will Cambodia ever be able to function independently, free of any influence from foreign powers?

No, of course not. It has never been able to do that, except back in the Angkorian era when it was the major power itself. Then there were no other major powers messing with it. Then there were no other major powers messing with it. But as soon as it became weak in the 16th and 17th centuries, it’s always been under the influence of one foreign government or another, and the governments of Cambodia have sought powerful patrons to protect them against other people they are frightened by or annoyed by.

But as soon as it became weak in the 16th and 17th centuries, it’s always been under the influence of one foreign government or another, and the governments of Cambodia have sought powerful patrons to protect them against other people they are frightened by or annoyed by.

So, they always had a patron of one kind or another, France or China—never had the United States, but they had various patrons. That’s a pattern that Hun Sen is following with the Chinese arrangement.

You seem very pessimistic.

I am afraid I am. I haven’t always been. I am not a pessimist by nature. I’d hate to have this broadcast be an expression of profound pessimism or anything, but I just don’t see where, in the near future, changes are going to take place. In 20 years, I have no idea. The world is going to be very different in 20 years. There will be a couple of billion people more on it. You know, it is going to be a different place.

With decades of wars and conflicts, how can Cambodia change its future for the better without shedding more blood?

Well, I can’t predict things. There are things that I just don’t know what’s going to happen. Let’s say the current leadership just dies peacefully, as I expect he will. What happens next? I am not sure. That’s when you could be able to see what the country is doing that might be different from him. I think that might be less personalized, but I think it is certainly going to be the same people who are going to be in power in Cambodia as are in power now. These are the investors, and the people with strong interest in remaining in power are not going to change. But maybe the manner and the style might change a little bit, might become just a little less personal, but I can’t say. Maybe not.

If you were to write another history book on Cambodia, what would you envision the book would be about?

Well, it would be about Cambodia’s past. I don’t want to predict Cambodia’s future. It’s not correct for me to even try to predict. I’m not a Cambodian. I can’t influence the choices. I am not going to tell or suggest to the Cambodians what they should do. But I think the last chapter of my history, if I do get a revised edition, will be more pessimistic than the last chapter was in the last edition.

But I think the last chapter of my history, if I do get a revised edition, will be more pessimistic than the last chapter was in the last edition.

You’ve just been honored with the “Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies” award yesterday and the president of the Association of Asian Studies said, “The work of David Chandler has made Cambodia a field of study.” What’s your comment on that?

Well, I didn’t make it a field of study, but people followed me into it. When I started in Cambodian history, there was no one else doing that. With the civil war, the Khmer Rouge, the refugee issue, UNTAC, a lot of people became involved in Cambodia outside the academic world, and a lot of them moved into academia after that, and became attracted to the country with UNTAC or the refugee [issue]. And it just became a much larger and more crowded—happily crowded—field, and I’m happy to have been, maybe, there the longest, but I didn’t create it. A mass of people joined after I was there already. I helped some of these people. Some of my students were some of these people, and I was happy to do that.