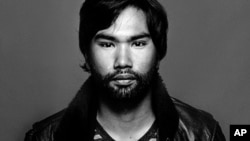

Pete Pin is a Cambodian-American documentary photographer based in New York. He is currently at work on a long term project to chronicle the lives of Cambodians in America. But Pin says the project, called “Displaced,” is also an exploration of psychological disconnection and the legacy of the Khmer Rouge.

The thirty-year-old photographer is searching for his heritage amid the Cambodian enclaves of America. Along the way, he is documenting dislocation. Most recently that has been in the Bronx, New York City.

“There’s a very amazing sense of community in the Bronx, but you see it in people’s homes, and you see it isolated in certain areas,” he said on a recent afternoon at a Cambodian temple in the Bronx.

Isolation is a recurring theme in Pin’s photographs -- from California, where he grew up, to Philadelphia, New York and other corners of America. In his images are scars, fleeting glances, backs turned, a figure glimpsed through a gossamer curtain. In many of them is a sense of stark disconnection.

“And I'm trying to use photography as a means to have that conversation,” he said. “But the photos are a manifestation of my own generational, cultural and historical displacement.”

Only a few hundred Cambodian families live in the Bronx. The temple Pin had come to is a main center of worship for them. It was the Cambodian New Year, and three boys were taking a quick lesson in Khmer from the temple monk, slowly scrawling the language of their motherland in a notebook. Pin pulled his camera from a black bag and began shooting, as Cambodian women chatted over food in the back of the room.

These are the moments Pin seeks to capture. He is in the process of putting together a growing exhibition—for Cambodians in America, or back home, and for anyone who may not understand the difficulties Cambodian refugees have had in the US.

But Pin, the son of parents who survived the Khmer Rouge, also shoots to find a part of himself.

“I can't say myself that I'm physically displaced, because I’m not,” he said. “I’m American; this is my home. But I am culturally displaced. I exist in this vacuum of identity, where I don’t know what it means to be either fully American or Cambodian. And in addition to that, there’s this legacy that I have in my heart and on my shoulders that was given to me at birth as a result of what my parents lived through. And I am trying for most of my adult life to really understand what that means.”