Although relations between Washington and Phnom Penh have been strained amid Cambodia’s growing friendship with China, Cambodian Americans still see a key role for the United States in demanding respect for democracy ahead of July’s national parliamentary elections.

Cambodia’s National Election Committee last month announced that the main opposition Candlelight Party was not eligible to participate in the election due to losing a registration document from the 1990s, a decision upheld by the country’s Constitutional Council.

The U.S. State Department issued a statement on May 25 saying it was “deeply troubled” by the move.

“Contrived legal actions, threats, harassment, and politically motivated criminal charges targeting opposition parties, independent media, and civil society undermine Cambodia’s international commitments to develop as a multiparty democracy,” said State Department spokesman Matthew Miller.

A number of politically engaged Cambodian Americans who spoke to VOA Khmer this past week said they were heartened by the statement, however some said they want to see deeper involvement from the U.S. in the final weeks before the July 23 ballot.

“Personally, I would like to see the United States not only issue statements of condemnation and then disappear. I want the U.S. to keep an eye on it because the U.S. is the father of democracy in the world,” In Suon, a social worker in Stockton, California, and a former supporter of the main opposition party, Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), told VOA Khmer.

He urged the Cambodian government to adhere to the Paris Peace Accords – an international agreement that in 1991 brought relative peace to the country after years of war and civil strife -- and Cambodia’s Constitution, which require a representative, multi-party democracy and the promotion of democracy and respect for human rights. But In Suon said that wouldn’t happen without external pressure to counter the government’s “tendency” to follow countries like China.

“When the liberal countries back off…then the people will lose more freedom,’’ In Suon told VOA Khmer by phone. “Therefore, I beg the government of the great power, the free world, do not back off, to join the negotiations to do that as much as possible.”

Amid the public posturing ahead of the July election is speculation about whether secret talks are playing out behind closed doors. Perhaps the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) will announce some major concession to create some semblance of a free and fair election. It’s happened before.

Just days before the 2013 national election, which would become the most competitive in decades, longtime opposition leader Sam Rainsy was allowed to return to the country, setting off a wave of excitement that nearly knocked off the CPP.

However, this year’s election comes amid a wave of oppression — as many of the country’s most prominent union leaders, activists and dissidents have been jailed or silenced through intimidation. Thach Setha, one of Candlelight Party’s vice presidents, remains jailed on charges the party claims are politically motivated.

Cambodian Americans say they just want for Cambodia what they have in America — an election where the most popular party can win.

“For us, we want the election to be fair and the way to organize the elections have to be fair,” Tung Yap, president of Cambodian Americans for Human Rights and Democracy in northern Virginia, told VOA Khmer.

“We do not care which party the people vote for, which candidate, we just want the people to be free to choose the individual or the candidate and a favorite party.”

Tung Yap, whose group recently hosted Rainsy for an event in Falls Church, Virginia, said an undemocratic election would inevitably harm US-Cambodia relations.

“When Cambodia does not practice democracy properly or does not respect human rights properly, United States officials find it difficult to work closely with Cambodian officials, or do business, or have good relations with Cambodia, because it contradicts their value,” he said.

However, the U.S. has cultivated warm relations with Cambodia’s communist neighbor in Vietnam, as well as authoritarian regimes from Saudi Arabia to Eqypt, due to geopolitical incentives ranging from energy to national security.

Touch Vibol, who is president of Cambodia-America Alliance (CAA) in High Point, North Carolina, said the U.S. should stay out of Cambodian politics and focus on areas like trade, education and health care.

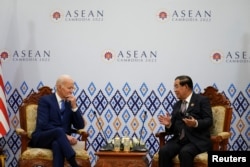

Otherwise, he said, Washington risks pushing Phnom Penh further into the arms of Beijing. Statements like the one issued by Miller last month will undermine broader U.S. efforts to expand its influence in Southeast Asia, where the ASEAN countries operate by consensus, Touch Vibol argued.

“That is why I want to emphasize that the United States still needs Cambodia, so avoid issuing any statement in the form of confrontation, it is necessary to show the image of cooperation, respect for the sovereignty of Cambodia, it is more profitable,” he said.

Touch Vibol was an adamant supporter of the opposition until this year, when he began supporting the CPP, which he says has the experience and capacity to lead the country

In its statement last month, the U.S. State Department said it would not send official election observers to monitor an electoral process “that many independent Cambodian and international experts assess is neither free nor fair.” And it urged Cambodian authorities to reverse course and allow the Candlelight Party to participate.

The CPP currently holds all 125 seats in the National Assembly, bolstering criticism that Cambodia has effectively become a one-party state. While there are other smaller parties registered for July’s election — including the royalist Funcinpec party — none had garnered the support or excitement of the Candlelight Party, which performed relatively well in 2022’s commune council elections, in a challenging, competitive environment.

While there is little doubt about who will win July election, especially without Candlelight in the picture, observers will keep a close eye on turnout among the 9.7 million registered voters as a measure of public disenchantment with the political process.

The election also marks a turning point for the CPP. Prime Minister Hun Sen’s eldest son, Hun Manet, is officially entering the political arena, as the ruling party’s top National Assembly candidate in Phnom Penh. The CPP has already approved his eventual accession to prime minister. And Hun Sen’s recent reassurance that he will remain in control of the political arena as president of the CPP has fueled speculation that Manet’s promotion could come soon after the election.

Time will tell whether Hun Manet takes a different approach to democracy from his father. But without any major developments in the coming weeks, the short-term outlook for the opposition looks bleak.

Rainsy, who has been effectively exiled, recently visited Washington DC to bring attention to what he calls a sham election, while fellow opposition leader Kem Sokha was sentenced to 27 years in prison on a treason conviction in March, and placed under indefinite house arrest.

Larry Seng, a Cambodian American supporter of Candlelight party, who lives near Seattle, Washington, said he has been saddened by the latest developments.

“Because democracy requires competition, and competition must be fair with equal strength, and when it comes to restricting the freedom of parties with similar strength to compete, it means that there is serious injustice,” he said.

“And I am very sorry that the freedoms of the Cambodian people have been restricted and they don’t have the right to choose a leader freely and fairly,” said Larry Seng.

Un Sokhom, a Cambodian American in Lowell, Massachusetts, told VOA Khmer that he believed the U.S. and other signatories of the Paris Peace Accords would assess the situation and pressure Cambodia’s government to fulfill its obligations.

“In the past that respect was not right, and the pressures against the ruling party happened to prevent the mistreatments of the people and the opposition,” he said.

Un Sokhom was involved in the founding of the opposition movement in 1997 but quit politics in 2012. He said he wants to see the current opposition leaders do more to restore democratic space in the country. If they do, he said he’d consider getting involved again.

“We can go in and have the desire to go back, but we are studying the political turn of Cambodia and looking for clear political principles.” If they become apparent, he said, “we will join.”