PHNOM PENH — On January 7, Prime Minister Hun Sen rode into Phnom Penh’s old Olympic Stadium in an open-top Mercedes and waved at the 50,000-strong crowd that had gathered to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the toppling of the Khmer Rouge regime by the Vietnamese army and units of Cambodian soldiers it supported.

In an address following a grand performance with traditional Khmer dancers and other performers, the premier hammered home the long-standing political message that his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) defeated the “genocidal regime” of Pol Pot and has brought peace and development to Cambodia since it was installed by Vietnam in 1979.

Meanwhile, in Vietnam, state-controlled media also commemorated the anniversary of the invasion - which was followed by a decade-long, bloody occupation - as a just “people’s war” that liberated Cambodians and secured lasting friendship between the neighboring countries.

In a twist of political history, however, the erstwhile communist brothers-in-arms these days find themselves in an increasingly strained relationship, as the CPP government has grown heavily dependent on economic and military support from China – the Khmer Rouge’s one-time backer and Hanoi’s traditional adversary.

As if to signal an historical turn, just two days after the grand memorial event three large Chinese warships reportedly docked in southwest Cambodia’s Sihanoukville Port. Hun Sen is scheduled to visit Beijing this month – one of several trips to China in recent years – while the countries’ fourth annual ‘Golden Dragon’ joint military drill in Kampot Province in March reportedly will be the largest yet.

The extent to which Cambodia and Vietnam’s “traditional friendship” is at risk of being undone by these developments will depend on how China chooses to use its influence in Cambodia and how Cambodia responds, analysts said.

There are signs of tensions in the Hanoi-Phnom Penh relations.

Border spat reveals neighborly tensions

An unreleased diplomatic notice obtained by VOA shows that unresolved border issues last year burst in open disagreement after the Vietnamese Army unilaterally planted pillars along a contested stretch of border off the Cambodian coast.

In the demarché to the Vietnamese Embassy dated July 23, 2018, Cambodia’s Foreign Ministry demanded that Vietnam remove border pillars constructed a few weeks earlier in an undelineated maritime border area.

The notice alleges that “many Vietnamese soldiers” and a barge carrying construction workers had placed “4 steel and 3 concrete piles” in the sea near Koh Ses, a small Cambodian island situated between southwest Cambodia’s coast and Phú Quõc, a large Vietnamese island once claimed by Cambodia. Koh Ses is also known as Koh Seh.

Phnom Penh “firmly protests” the actions, demanded the pillars removal, and noted that it was “contrary to cooperation framework” the countries had signed, it reads.

VOA was unable to reach the Foreign Ministry for comment on the diplomatic notice. An official in the coastal province of Kep, who requested anonymity as the official was unauthorized to comment, said the local situation had “calmed” and the national government was in talks with Vietnam about the pillars.

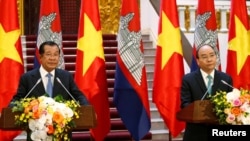

During what appeared to be a visit to Hanoi to ease relations in December, Hun Sen met Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc and General Secretary of the Communist Party and President Nguyen Phú Trọng. They agreed to “work to settle issues on the shared border” and on “legalizing 84 per cent of the border demarcation and marker planting related work,” Vietnamese state-controlled media reported.

No mention was made of the disagreement over Vietnam’s pillar construction and it remains unclear whether it has agreed to Cambodian demands for their removal.

A need to balance foreign relations

Elliot Brennan, research fellow at the Institute for Security and Development Policy in Stockholm, said such rising tensions over the old grievance of border demarcation would benefit China and could be the result of its growing influence in Cambodia.

Cambodia and Vietnam, he said, “need to elevate border cooperation to the highest importance in the relationship and set out an achievable roadmap to settle disputes and improve the relationship past old grievances.’’

“This will strengthen Cambodia’s negotiating power with China, as it heals an old wound [in relations with Vietnam] that some domestic and foreign actors are keen to aggravate for political gain,” Brennan told VOA Khmer.

The CPP government has long sought to keep a check on historic anti-Vietnamese nationalism in Cambodia. It kept sensitive border demarcation discussions out of public view to avoid former opposition leader Sam Rainsy tapping such sentiments by claiming that Hun Sen is losing territory.

Analysts said Cambodia is in need of a flexible foreign policy that builds relations with many countries and reduces the diplomatic reliance on China.

“Hun Sen, who has shown himself a shrewd diplomatic actor over decades and who understands the importance of ‘hedging’ between influential actors, should aim to rebalance Cambodia’s diplomatic and trade relations both within ASEAN and abroad,” Brennan said.

Many Asian countries, including Vietnam, welcome the benefits of stronger economic and military bilateral relations with China, but they generally work simultaneously with other smaller countries and in regional cooperation to resist Beijing’s attempts to establish hegemony in Asia, analysts said.

Carlyle Thayer, a Vietnam expert at the University of New South Wales in Australia, said Vietnamese leaders were “relatively relaxed” about Cambodia’s tightening relations with Beijing as Hanoi, too, had improved its relations and military cooperation with China, while Vietnam-Cambodia defense cooperation continued.

Cambodian subservience to China would ‘contain’ Vietnam

Nguyen Khac Giang, senior political researcher at the Vietnam Institute for Economic and Policy Research in Hanoi, however, stressed the importance of an independent Cambodian foreign policy for the neighborly relations.

“It is significant for smaller countries to keep well balanced among powers in the region,’’ Nguyen Khac Giang told VOA Khmer. “An independent, open, and prosperous Cambodia would not only benefit Cambodians, but also the Vietnamese.”

Cambodia’s tightening embrace with Beijing, and its support for Chinese territorial claims that affect Vietnam and other countries in the South China Sea, raise questions as to whether Cambodia is keeping such a balance.

Nguyen Khac Giang warned that while a lack of independent Cambodian foreign policy could affect relations, outright Cambodian acceptance of China’s plans for regional dominance would be viewed by Vietnam as a strategic threat.

“The Vietnamese-Cambodian relationship is of critical importance to Hanoi not only because of historical reasons,” he said. “Cambodia and Laos are [Vietnam’s] strategic partners and allies, and their only neighbors [along with China], therefore if those two countries are pro-Beijing it would leave Vietnam inside China's containment.”

Such concerns over possible Cambodian subservience to China have drawn international attention following a sharp increase in Chinese loans and investment as well as military cooperation in recent years.

Hun Sen denies Chinese base claims

This led to rumors that a Chinese base was being established on the Cambodian coast – a claim that Hun Sen opted to publicly deny.

Sihanoukville port – located some 50 kilometers west from where the Vietnamese border pillars were allegedly constructed – has become a site of frequent visits by the Chinese navy and massive Chinese infrastructure and real estate investment for beach tourism.

Located on the Gulf of Thailand, the port has become part of China’s strategic Belt And Road Initiative, and a huge Chinese-leased land concession nearby has fuelled speculation that Beijing is constructing a naval deep-sea port in the area.

During his Vietnam visit in December, Hun Sen saw it necessary to tell a press conference that “Cambodia did not need and Cambodian constitution did not allow the establishment of foreign military bases in its territory,” according to Vietnamese state-controlled media.

Hun Sen also said he would inform U.S. Vice President Mike Pence that the claim was false. Relations between Phnom Penh and Washington have deteriorated significantly as a result of China’s rising influence and the CPP’s victory last year in an election that was seen as neither free nor fair.

Despite such strains on the neighborly relations, Thayer, the Vietnam expert, argued that for now Vietnamese leaders appear not too worried about China’s heavy presence next door.

“Vietnamese leaders know Hun Sen quite well and are willing to work with him and his successors as long as Cambodia does not act directly against Vietnamese interests,” Thayer said. “In sum, Vietnam does not want a single issue – such as disagreement over the South China Sea – to hold the larger bilateral relationship hostage.”

(Correction: The earlier version of this article quoted Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation's demarche sent on July 23, 2018 to the Embassy of Vietnam in Phnom Penh identifying the Vietnamese military buildups as "pillars", which was not correct. The correct one from the aforementioned diplomatic notice identifies the construction as "piles".)