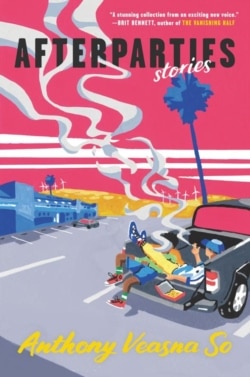

WASHINGTON D.C. — A new book by Anthony Veasna So is being hailed as an exciting and highly original work of literary fiction that captures what it is like to grow up in contemporary American society as a child of Cambodian refugees.

The book is being widely praised by literary critics and welcomed by the Cambodian-American community for its vivid descriptions—full of humor and compassion—of families grappling with the traumas of Khmer Rouge survival, while also navigating the cultural dislocation and socio-economic challenges of refugee resettlement.

As The New Yorker magazine observed, “Classics of immigrant storytelling can feel sparse and solemn. The stories in So’s [book] ‘Afterparties’ fill the silence, spilling over with transgressive humor and exuberant language.”

I had grown up hearing the stories of the genocide, worked to help build our new American identities, and mourned, alongside everyone else in my family, the gaps in our history that could never be recovered.

Written from the perspectives of young Cambodian-Americans, So’s collection of short stories, called “Afterparties,” offers a fresh look at the contemporary experience of this second generation of the Cambodian diaspora.

Until now, most depictions of Cambodians in English-language writing and film are memoirs and non-fiction books, and few well-known movies, which focus on the older generation’s dramatic stories of surviving the killing fields and their refugee journeys to Western countries.

“Afterparties” was recently launched with much fanfare by well-known American literary house Ecco, which printed 100,000 copies after it reportedly signed So on a $300,000-deal for two books. (Another book based on segments from an unfinished novel is expected in 2023).

Sadly, So did not live to see his first book published, as he died in December 2020 at his home in San Francisco of an accidental drug overdose. He was 28.

The New Yorker, which first published some of his early stories, described So’s death as “cutting short a literary career of extraordinary achievement and immense promise.”

A Washington Post review wrote: “‘Afterparties’ insists on a prismatic understanding of Cambodian American diaspora through stories that burst with as much compassion as comedy, making us laugh just when we’re on the verge of crying.”

“It is this ability to make pain shape-shift into the hopeful and the hilarious that makes So’s work so compelling.”

‘Post-khmer genocide queer stoner fiction’

His writing captures the second generation’s perspective on the effects of lingering trauma and other issues at the heart of Cambodian-American community, such as family, friendship and religion (delving into Buddhist beliefs about reincarnation, for instance). He also touches on more common issues such as the contemporary complexities of race, youth and sexuality.

So, who was gay, reportedly once described his own work as “post-khmer genocide queer stoner fiction.”

As any Cambodian born to Khmer Rouge survivors will tell you, the horror stories and traumas inflicted by the murderous 1970s regime are an inseparable part of growing up in a Cambodian family.

Sometimes, parents will relate a survival story with a life lesson for a child or adolescent, or they may talk about their experiences in a more light-hearted way, other times they may simply need somebody to listen to their past experiences or feelings.

"Reading through ‘Afterparties,’ it was so resonant, it was so refreshing, to see the Cambodian diaspora, which is not represented in literature—apart from the survival literature."

So’s sharp observations about his parents’ coping mechanisms and traumas, and its effects on their children, offer an unflinching look at the multi-generational impact of war and violence. Yet, he never overlooks the humor and absurdity of some of the situations this creates for the second generation, who are growing up in modern America, 10,000 miles away from Cambodia.

In one of the stories, a father scolds a teenager who drinks ice water, and shouts: “There were no ice cubes in the genocide!”

‘Afterparties’ contains nine short stories, including “The Monks,” about a son who has to spend time at a Buddhist pagoda after his father died and “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly,” a story about reincarnation set in an Alzheimer’s and dementia unit. “Generational Differences” is about a 1989 mass shooting at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, in which predominantly children of Southeast Asian descent were shot and five were killed. (So’s mother worked at the school and witnessed the violence.)

Previously, So published in various outlets, including a 2018 story in n+1 Magazine called “Superking Son Scores Again,” about a legendary badminton player turned grocery store owner who tries to relive his glory days. A 2020 story in The New Yorker called “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” centers on two sisters working in their family’s donut shop who are intrigued by a mysterious customer.

n+1 Magazine recently launched a literary award called “Anthony Veasna So’s Fiction Prize” in his honor and its first recipient is Trevor Shikaze, a writer for n+1 from Canada.

Mark Krotov, the magazine co-editor and publisher, told VOA Khmer that So’s work would likely impact many young writers. “There is so much wisdom in it, there is so much adventure… so much risk-taking, so much beauty, so much intelligence, so much provocation. And all those things in combination suggests to me that this is the book that’s going to be remembered,” Krotov said in a recent phone interview.

A literary depiction of the Cambodian-American experience

So’s parents fled northwestern Cambodia’s Battambang Province and settled as refugees in the quiet city of Stockton in central California, where his father ran an auto repair shop and his mother worked as a civil servant. So was born in Stockton in 1992.

Cambodian-American intellectuals said So’s fiction masterfully conveyed their experiences, family life and sense of community.

“He writes the voices of our Cambodian elders in a way that just feels so accurate… I was always thinking like: ‘Yeah, I do know any auntie like that, I know an auntie who thinks she knows how I should live my life,’” Monica Sok, a poet who was a friend of So, told a recent panel discussion at Book Passage, a Bay Area bookstore.

“Reading through ‘Afterparties,’ it was so resonant, it was so refreshing, to see the Cambodian diaspora, which is not represented in literature—apart from the survival literature,” Sok said.

“Anthony is really centering Cambodian people in America and the second generation as well, those who are born in this country and inheriting their parents’ traumas, but also trying to find their own way in life.”

Sokunthary Svay, a Cambodian-American writer and librettist from New York City, also admired So’s work and its depictions of her community, such as the traditions and celebrations like Khmer weddings.

“I think what makes his writing particularly important for our diaspora is that he would speak about experiences that a lot of us knew growing up here in the States,” she told VOA Khmer.

"I think it is about his writing style where it kind of combines humor with high art and with low art."

According to his sister, Samantha Lamb, So loved television shows and movies and he discovered his talent while trying to write a script for a television show about a Cambodian-American family, which he based on his own life.

“When I read the stories, I was like, oh you know, okay yes yes, that is the story about my grandma’s sister, that’s the story about my aunt. This person represents this person in my family,” Lamb told VOA Khmer.

So is from a large family and all the children were high-achieving students. He graduated from Stanford University and earned his Master of Fine Art in Fiction at Syracuse University. Before realizing that writing was his passion and talent, he studied computer science but he dropped out and changed course, to the initial dismay of his family.

Lamb noted that So visited Cambodia twice when he was about 10 and 15 years old.

‘Stories of the Cambodian genocide, but from a young person perspective’

Lamb said Khmer Rouge-era experiences are a recurrent theme in his writing as “it is a big part of who we are and growing up my parents talked about it all the time.

“They don’t want to go to see a counselor and that affects me because sometimes they need to talk to somebody about what they went through. But then they come out on me as a child because parents whatever happened to them as a kid—they perpetuate—they actually do those things to their kids,” she told VOA Khmer.

So wrote, in a story published in The New Yorker called “Duplex”: “I had grown up hearing the stories of the genocide, worked to help build our new American identities, and mourned, alongside everyone else in my family, the gaps in our history that could never be recovered.”

Lamb said her brother, nonetheless, found a new way to process this painful family history and turn it into a new, contemporary experience, rather than relying on the established language of survival memoires or narratives from historical movies.

“It tells the stories of the Cambodian genocide, but from a young person perspective,” Lamb said. “There hasn’t really been any book or movie or TV show about Cambodians in the Western eyes, you know in the American eyes, that has been about just like who we are as Cambodian Americans now. So, I think that what makes it more relatable to people.”

Alex Torres, So’s partner for seven years and also a writer, said that what makes his writing special are “the humor, the lightheartedness, the jokes, but also the really beautiful descriptions.”

“I think it is about his writing style where it kind of combines humor with high art and with low art,” he told VOA Khmer.

According to Lamb, the family is still struggling with the grief of his loss, though they are immensely proud to see his writing being so well received. His father sleeps in So’s bed to console himself, while his mother is going to a therapist and their grandmother is claiming he may get reincarnated soon.

“I am pregnant right now,’’ Lamb said, ‘’and it is a boy… and especially my grandma has been like ‘Oh! Anthony is coming back. He is being reincarnated.’”