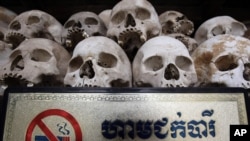

ODDAR MEANCHEY Province - In an effort to prevent future atrocities like those conducted under the Khmer Rouge, the Documentation Center of Cambodia has been erecting memorials at high schools across the country. The memorials are meant to prompt discussion of the regime, in hopes of more national reconciliation.

One of these memorials was erected last month in the final stronghold of Democratic Kampuchea, as the Khmer Rouge is formally called, in the northwestern part of the country, Anlong Veng, in Oddar Meanchey province.

The memorial, a black marble plaque with gold lettering, was mounted on the wall at Anlong Veng High School. It has messages that read, “Learning about the history of Democratic Kampuchea is to prevent genocide,” and, “Speaking about experiences during the Democratic Kampuchea regime is to promote reconciliation and to educate children about forgiveness and tolerance.”

Dy Khamboly is the team leader of Anti-Genocide Education Project at the Documentation Center of Cambodia and the author of a history book on the regime that is now taught in some schools.

“The ultimate aim of learning the history of Democratic Kampuchea is to contribute to permanent national reconciliation in Cambodia, as well as genocide prevention and the building of longterm peace in the future,” he told VOA Khmer.

In this remote jungle district, the final holdouts of the regime finally folded into the government in 1999. Many here are former cadre of the regime, or their relatives.

Some raised objections to the teaching of Khmer Rouge history, which is why a memorial is important to have here, Dy Khamboly said.

“It is not meant to make old wounds reappear, nor to provoke anger or revenge,” he said.

Across the street from the high school, Um Mek tends his shop. He said he is not among the detractors of the plaque.

“The memorial creates tolerance for each other,” he said. “Learning about Khmer Rouge history is not to take revenge but to know about the society then.”

Back at the school, students like Phann Pisey, who is a 10th grader, took part in the inauguration ceremony. Cambodian youth have little understanding of the regime, its history and its atrocities, because until recently it was not taught in school, and their parents are loathe to talk about their traumatic experiences from the past.

“As a student, having learned about the regime,” Phann Pisey said, “I feel I want to learn about it and to know what happened in the past.”

The regime’s leader, Pol Pot, died here in Anlong Veng in 1998. His cremation site here is now a tourist attraction. Researchers say that some residents here still do not consider the Khmer Rouge a genocidal regime, though others have expressed feelings of guilt and shame for crimes they committed under its authority.

Yim Phanna is a former Khmer Rouge commander who is now the governor of Anlong Veng. He said the memorial is a reminder of a past regime that caused destruction, separation and the loss of lives.

“We still have regrets,” he said. “The regime should never have happened, so we need to promote an understanding of the regime more broadly so that it won’t exist to ruin our society again.”

Ton Sa Im, an undersecretary of state for the Ministry of Education, who also attended the inauguration, said during the ceremony the integration of Anlong Veng into Cambodia set a proper example of reconciliation.

“There should be no revenge or fingers pointed to each other, that this person used to be red, blue, or white back then,” she said. “Now we have the same color, and together we need to work for a common goal.”

One of these memorials was erected last month in the final stronghold of Democratic Kampuchea, as the Khmer Rouge is formally called, in the northwestern part of the country, Anlong Veng, in Oddar Meanchey province.

The memorial, a black marble plaque with gold lettering, was mounted on the wall at Anlong Veng High School. It has messages that read, “Learning about the history of Democratic Kampuchea is to prevent genocide,” and, “Speaking about experiences during the Democratic Kampuchea regime is to promote reconciliation and to educate children about forgiveness and tolerance.”

Dy Khamboly is the team leader of Anti-Genocide Education Project at the Documentation Center of Cambodia and the author of a history book on the regime that is now taught in some schools.

“The ultimate aim of learning the history of Democratic Kampuchea is to contribute to permanent national reconciliation in Cambodia, as well as genocide prevention and the building of longterm peace in the future,” he told VOA Khmer.

In this remote jungle district, the final holdouts of the regime finally folded into the government in 1999. Many here are former cadre of the regime, or their relatives.

Some raised objections to the teaching of Khmer Rouge history, which is why a memorial is important to have here, Dy Khamboly said.

“It is not meant to make old wounds reappear, nor to provoke anger or revenge,” he said.

Across the street from the high school, Um Mek tends his shop. He said he is not among the detractors of the plaque.

“The memorial creates tolerance for each other,” he said. “Learning about Khmer Rouge history is not to take revenge but to know about the society then.”

Back at the school, students like Phann Pisey, who is a 10th grader, took part in the inauguration ceremony. Cambodian youth have little understanding of the regime, its history and its atrocities, because until recently it was not taught in school, and their parents are loathe to talk about their traumatic experiences from the past.

“As a student, having learned about the regime,” Phann Pisey said, “I feel I want to learn about it and to know what happened in the past.”

The regime’s leader, Pol Pot, died here in Anlong Veng in 1998. His cremation site here is now a tourist attraction. Researchers say that some residents here still do not consider the Khmer Rouge a genocidal regime, though others have expressed feelings of guilt and shame for crimes they committed under its authority.

Yim Phanna is a former Khmer Rouge commander who is now the governor of Anlong Veng. He said the memorial is a reminder of a past regime that caused destruction, separation and the loss of lives.

“We still have regrets,” he said. “The regime should never have happened, so we need to promote an understanding of the regime more broadly so that it won’t exist to ruin our society again.”

Ton Sa Im, an undersecretary of state for the Ministry of Education, who also attended the inauguration, said during the ceremony the integration of Anlong Veng into Cambodia set a proper example of reconciliation.

“There should be no revenge or fingers pointed to each other, that this person used to be red, blue, or white back then,” she said. “Now we have the same color, and together we need to work for a common goal.”