Britain has summoned the Chinese ambassador after he said that relations between Beijing and London had been "damaged" by Britain's backing of pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.

Ambassador Liu Xiaoming warned Britain not to interfere in what he called China's "internal affairs." Earlier, British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt offered his strong backing for the demonstrations in Hong Kong, which was a British territory until the handover of power to China in 1997.

"The UK signed an internationally binding legal agreement in 1984 that enshrines the 'one country, two systems rule,' enshrines the basic freedoms of the people of Hong Kong and we stand four square behind that agreement, four square behind the people of Hong Kong. And there will be serious consequences if that internationally binding legal agreement were not to be honored," Hunt said Tuesday.

The United States and its allies have also voiced grave concern over the direction of Chinese rule in Hong Kong.

Pro-democracy supporters are urging Britain to do more, claiming it has a legal and moral duty to stand up for the freedom of Hong Kong's people.

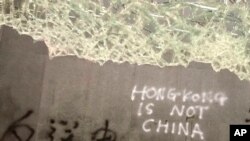

The Union Jack flag has been a prominent symbol amid weeks of pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong. Violent protests marked the 22nd anniversary of handover to Chinese rule Monday, as demonstrators stormed the parliament building.

The protests were triggered by an attempt to force through an extradition bill allowing Hong Kong suspects to be prosecuted in mainland China. Critics say the law could be used to send political dissidents to China for prosecution.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang condemned Britain's intervention Wednesday.

"The U.K. placing itself as the protector [of Hong Kong] at every turn is a purely self-constructed delusion. I would like to ask Mr. Hunt, during the British colonial era in Hong Kong, was there any democracy to speak of? Hong Kongers didn't even have the right to protest."

Beyond Sino-British relations, there are wider implications for Beijing, says Professor Steve Tsang of London's School of Oriental and African Studies.

"The key issue here really is not about our [Britain's] obligations to Hong Kong,” Tsang said. “It's also about how China deals with international agreements.”

The 1997 handover was widely seen as the final curtain call on the British Empire. The British governor of Hong Kong at the time, Chris Patten, wants London to do more.

"We should have a sense of honor about Hong Kong and we should have a specific sense of our obligations to the individual citizens of Hong Kong. And that means speaking up about what's been happening," Patten said in a recent interview.

However, Britain's options are limited because of the political chaos over its departure from the European Union, argues Tsang.

"China is a rising power and is potentially the second superpower. The UK is getting into a stage of uncertainty about its future. So we are not in a particularly strong position compared to China in trying to resolve any disputes we may have with China at the moment."

Beijing insisted Wednesday any foreign efforts to interfere in Hong Kong are, in its words, destined to be "futile."