Cambodia’s large and growing debt to its northern ally China is a growing concern for observers who worry about the undue influence this may afford the regional superpower.

By 2015, Cambodia had racked up about $2.7 billion worth of debts to China, according to Vongsey Vissoth, a secretary of state at the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

He claimed the loans China made to Cambodia came without strings attached and therefore left Cambodia open to fulfilling its democratic obligations, but analysts speaking to VOA Khmer begged to differ, saying that by not attaching aid and development lending to commitments to improve human rights and democratic process, it paved the way for rights abuses.

Kem Ley, a researcher and political campaigner, said Chinese investment and loans had helped Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government maintain its grip on power.

“Our government finds it’s hard to adapt to democratic principles. So they have to walk backwards. Walking backwards means that they need to depend on other nations which implement communist models. That's how they maintain their power – by relying on the superpower,” he said.

By closely allying with Beijing, he added, Cambodia had ignored relations with Taiwan and Hong Kong.

“The policy of saying China is the only one is a policy of deadlock. We are not able to connect with Hong Kong and Taiwan. That's the first thing I see. Second, China has to invest in order to gain ground in terms of geopolitics before reaching military geography to exert influence in the South China Sea dispute,” he said.

In recent years China’s global reach has extended across Asia, Latin America and Africa, where it has invested heavily in hydropower, mining and other development projects.

Western countries have in the past attached commitments to improving human rights and democracy as preconditions before handing out aid or offering loans.

The World Bank recently announced it was restarting lending to Cambodia after nearly five year of moratorium.

The country is also experiencing the worst drought in several decades, which has pushed it closer to China in a bid to boost its agriculture-based economy.

Heng Sreang, a political researcher, said the drought would cause Cambodia to request more loans from China.

“We are becoming poorer due to the drought and natural resource exploitation. So, they [the government] seems to put the fate of the nation into the loans obtained from China, without taking into account the impacts on the people or becoming a debtor,” he said.

“Mostly China tried to be a friend with some nations in Africa and Asia to make them its pawns or debtors. It is easy to use or go into those nations to extract minerals and invest in land or dams to serve its interest,” he said.

Kem Ley, a social researcher and political campaigner, said that Cambodia should seek to strike a better balance between Western and Chinese investment and lending.

“If we meet a dead end with China, not only do we suffer from debt crisis but also our politics and diplomacy will also meet a deadlock,” he said. “In general, we escape from the crocodile and get into the mouth of a tiger, meaning that we get away from the communist Vietnamese just to be in alliance with another communist nation.”

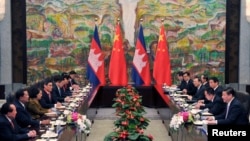

Newly appointed Foreign Minister Prak Sokhon, however, said after a recent meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, that Cambodia had maintained a neutral stance during China’s dispute with other Asean nations over the South China Sea.

“Therefore, the Cambodian stance is calling for the related parties to seek peaceful resolution through dialogue, negotiation and adhering to international law,” he said.

Ou Virak, head of the Future Forum think tank, said that, despite the minister’s comments, the country remained on course to remain a staunch China ally.

“It is a concern for us too due to the fact that if we rely on China too much, Cambodia could become a tool for China to use in many international disputes,” he said.

In 2012, Cambodia was criticized for failing to issue a joint statement related to the South China Sea dispute when Phnom Penh hosted the Asean Summit, the first time the body had failed to issue a statement after a summit since it was formed.

Heng Sreang said Cambodia should seek to emulate Singapore, which during the 1960s and 1970s morphed from a small post-colonial state into a regional financial powerhouse.